I grew up with both of my Persian Parents speaking Azeri at home (a language which is a combination of Persian and Turkish) and with a deep desire to learn and practice Persian but I didn't have much time, focus or tools to help me with becoming more fluent.

Thanks to the wonderful site called chaiandconversation.com I now have a community, course work and opportunities to practice Persian which has really liberated my soul from any shame. It has also delighted my Love for language, poetry and connection to an identity of being Persian which has been ever evolving.

I received my first bootcamp certificate of completion last spring and am now working on the fall bootcamp, join me in this wonderful Persian online community!

Something I have come to understand in learning languages and writing poetry is that our experience of life itself is determined by our usage of language and the words we choose. Certain languages and cultures experience life differently and express our experiences differently, simply by having different expressions of words. Here is what I have found around the differences between Persian and English.

Vocabulary and Emotional Nuances

English has a broad range of emotions related words, also having words that categorize emotions with more specifity. "Nostalgia" and "elancholy" are examples of very specific states (see part 2 where I go more into the emotion of "nostalgia").

In English we tend to use the word "Love" more broadly. We add adjectives to refine the type of Love into erotic love, platonic love, fraternal love or romantic love.

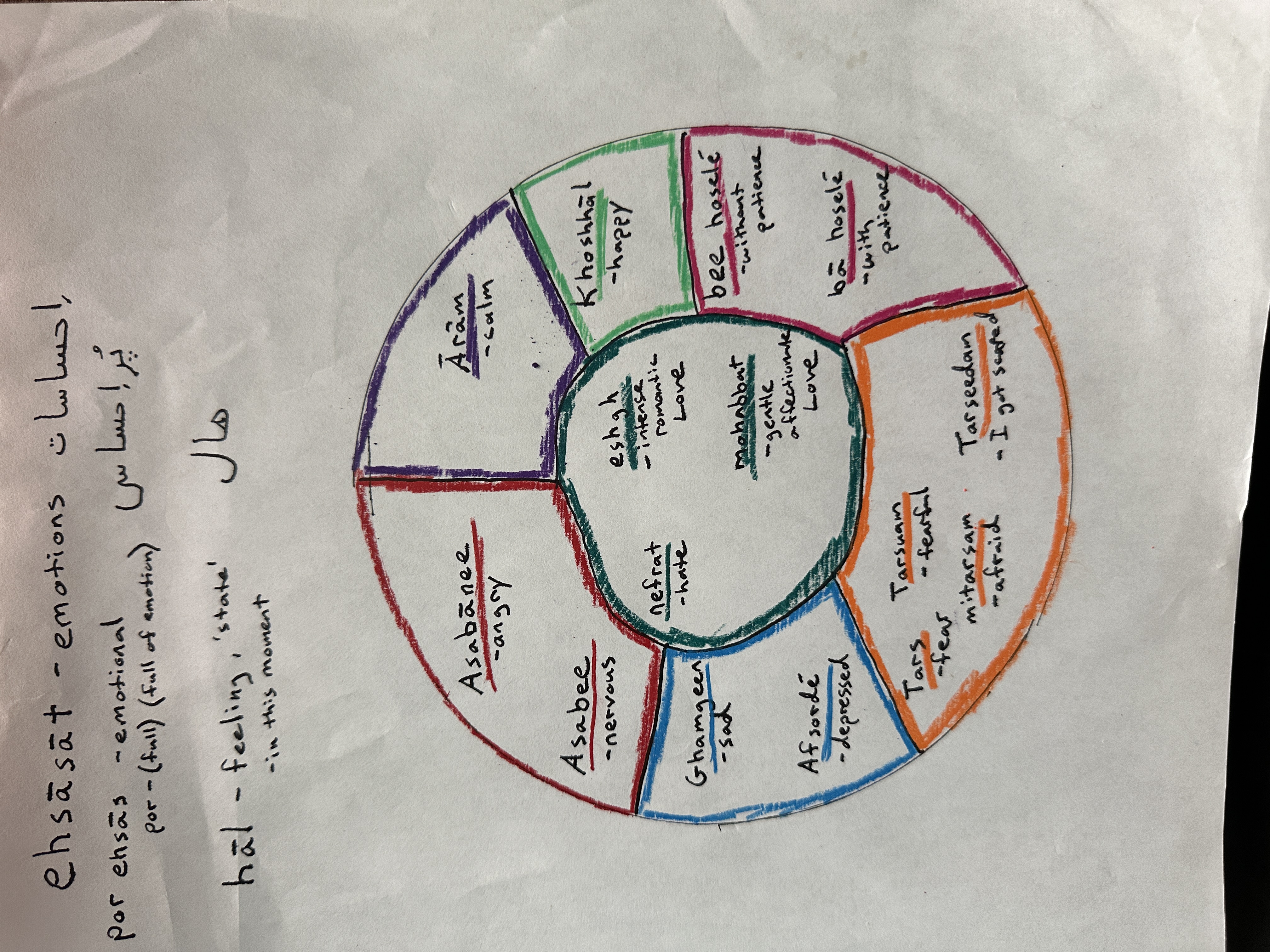

In Persian, عشق (eshgh) refers to intense, often romantic love, while محبت (mohabbat) conveys a gentler, affectionate form of love, similar to "affection" in English.

In Persian هال (hāl) meaning "feeling", also as in "state", in this moment. So asking someone "how are you?" is akin to "how is your condition?" or "how is your state of being?"

Cultural Context and Expression

In English speaking culture we often prioritize individual emotional expression. People are encouraged to openly express their feelings, such as happiness, anger, or love.

We tend to be more direct with emotional communication in English, with phrases like "I’m upset" or "I love you" commonly used in everyday interactions.

In Persian culture there is an emphasis on family and community. Emotional expression may be more subdued in public or formal settings to maintain social harmony.

Persian speakers often use indirect language and metaphors to express emotions. For instance, instead of saying "I’m sad," someone might say "My heart is broken (Delam shekasteh)" (دلم شکسته). This can soften the emotional expression and make it sound more poetic or polite.

Emotional Experience

In English we may tend to compartmentalize emotions more due to the specific terms available. For instance, differentiating between "annoyance," "frustration," and "anger" allows for a clearer understanding of the intensity of an emotion.

In Persian, emotional words, particularly those involving "del" (heart), tend to offer a more holistic view of emotions, integrating physical, emotional, and sometimes spiritual elements. The cultural emphasis on poetry and mysticism (e.g., through the works of Rumi or Hafez) enriches how emotions like love and sorrow are experienced.

Emotional Regulation and Social Norms

In English speaking cultures we often value emotional transparency. People are encouraged to share their feelings, for instance as in therapy or self-help contexts.

There is also a stoic tendency in some English cultures (like in Britain) where there might be more restraint in expressing negative emotions, favoring "keeping a stiff upper lip."

In Persian speaking cultures, people may regulate their emotions more carefully, especially in public settings. Negative emotions like anger or sadness might be toned down to avoid disturbing group harmony.

In more private or intimate settings (like family gatherings), emotions may be expressed more freely and even dramatically, particularly when it comes to mourning or expressing love.

Much of what I have shared in the above has been my own experience but also what others have reflected to me and what I have seen in my reading and studying of poetry, language and cultures; this may not be the experience of everyone in either the English or Persian speaking camps.

I'd like to turn back again to the most important book I have read this year called "Atlas of the Heart", to look more closely at some emotions in English and what research shows about these emotions.

Places We Go with Others

Compassion

Compassion is a daily practice and empathy is a skill set that is one of the most powerful tools of compassion.

Compassion is the daily practice of recognizing and accepting our shared humanity so that we treat ourselves and others with loving-kindness, and we take action in the face of suffering.

Empathy

Empathy, the most powerful tool of compassion, is an emotional skill set that allows us to understand what someone is experiencing and to reflect back that understanding.

There are two elements to empathy: cognitive empathy and affective empathy.

Cognitive empathy, sometimes called perspective taking or mentalizing, is the ability to recognize and understand another person's emotions. Affective empathy, often called experience sharing, is one's own emotional attunement with another person's experience.

We can respond empathically only if we are willing to be present to someone's pain. If we're not willing to do that, it's not real empathy.

Boundaries

Brene Brown writes that "the heart of compassion is really acceptance". The better we are at accepting ourselves and others, the more compassionate we become. If we really want to practice compassion, we have to start by setting boundaries and holding people accountable for their behavior.

Places We Go When We Fall Short

Shame

Oh boy, here we go.

Shame is the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love, belonging, and connection.

Shame thrives on secrecy, silence and judgment.

Connection, along with love and belonging (two expressions of connection), is why we are here, and it is what gives purpose and meaning to our lives.

Shame needs you to believe that you're alone. Empathy is a hostile environment for shame.

Shame is a social emotion. Shame happens between people and it heals betwen people.

Even if I feel it alone, shame is the way I see myself through someone else's eyes.

Kristin Neff has done a great deal of research on self-compassion and often self-compassion is the first step in healing shame.

According to Neff, self-compassion has three elements: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness..

Empathy:

is an other-focused emotion. It draws our attention outward, toward the other person's experience.

Shame:

is an egocentric, self-involved emotion. It draws our focus inward. Our only concern with others when we are feeling shame is to wonder how others are judging us. Shame and empathy are incompatible. When feeling shame, our inward focus overrides our ability to think about another person's experience.

Perfectionism

Perfectionism is exgternally driven by a simple but potentially all consuming question: "What will people think?"

One of the biggest parriers to working toward mastery is perfectionism. Acheiving mastery requires curiosity and viewing mistakes and failures as opportunities for learning.

Perfectionism is a self-destructive and addictive belief system that fuels this primary thought: If I look perfect, live perfectly, work perfectly, and do everything perfectly, I can avoid or minimize the painful feelings of shame, judgement, and blame.

"Life paralysis" refers to all of the opportunities we miss because we're too afraid to put anything out in the world that could be imperfect. It's also all of the dreams that we don't follow because of our deep fear of failing, making mistakes, and disappointing others.

Perfectionism is self-destructive simply because there is no such thing as perfection. Perfection is an unattainable goal. Additionally, perfectionism is more about perception- we want to be perceived as perfect.

Places We Go When We Search for Connection

Belonging

We have to belong to ourselves as much as we need to belong to others. Any belonging that asks us to betray ourselvecs is not true belonging.

True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn't require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.

Love and belonging are irreducible needs for all people. In the absense of these experiences, there is always suffering.

Belonging is a practice that requires us to be vulnerabile, get uncomfortable, and learn how to be present with people without sacrificing who we are.

Because we can feel belonging only if we have the courage to share our most authentic selves with people, our sense of belonging can never be greater than our level of self-acceptance.

Connection and Disconnection

Connection is the energy that exists between people when they feel seen, heard and valued; when they can give and receive without judgement; and when they derive sustenance and strength from the relationship.

Disconnection is often equated with social rejection, social exclusion, and/or social isolation, and these feelings of disconnection actually share the same neural pathways with feelings of physical pain.

Insecurity

The opposite of personal insecurity is self-security, "the open and nonjudgemental acceptance of one's own weaknesses." according to researchers Alice Huang and Howard Berenbaum.

We can have highg self-esteem but still be insecure if we're overly critical of our imperfections.

People who are more secure are more willing to be vulnerable with others. If we are comfortable with our own weaknesses (in other words, if we are self-secure), we are more successful at being emotionally close to others and more likely to have healthy relationships.

Invisibility

Invisibility is a function of disconnection and duhumanization, where an individual or group's humanity and relevance are unacknowledged, ignored, and/or diminished in value or importance.

Loneliness

Cacioppo and his colleague William Patrick define loneliness as "perceived social isolation".

At the heart of loneliness is the absence of meaningful social interaction- an intimate relationship, friendships, family gatherings, or even community or work group connections.

Being alone or inhabiting solitude can be a powerful and healing thing.

We don't derive strength from our rugged individualism, but rather from our collective ability to plan, communicate, and work together.

Hunger is a warning that our blood sugar is low and we need to eat. Thirst warns us that we need to drink to avoid dehydration. Pain alerts us to potential tissue damange. And loneliness tells us that we need social connection- something as critical to our well-being as food and water.

Unchecked loneliness fuels continued loneliness by keeping us afraid to reach out.

Numerous studies confirm that it's not the quantity of friends but the quality of a few relationships that actually matters.

Living with air pollution increases your odds of dying early by 5 percent. Living with obesity, 20 percent. Excessive drinking, 30 percent. And living with loneliness? It increases our odds of dying early by 45 percent.

That last statistic is from researchers Julianne Holt-Lunstad, Timothy B. Smith, and J. Bradley Layton.

In a 2017 Harvard Business Review article, Dr. Murthy writes, "During my years caring for patients, the most common pathology I saw was not heart disease or diabetes; it was loneliness."